Two years ago, at a conference in Atlanta, a woman from Jamaica excitedly approached me when she learned that my company provided experts for medical malpractice cases. She had been searching for resources to help in her efforts to support victims of medical malpractice in her home country. She shared multiple stories of negligence that were almost unimaginable and confided that although many Jamaican doctors were educated to North American standards, their underfunded, undersupplied and poorly managed public health-care system was struggling greatly, leaving too many patients injured as a result. There was little recourse for injured patients and minimal accountability for health-care providers.

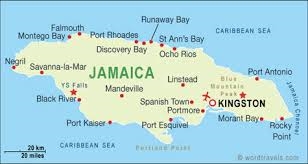

Doctors on the small island of 2.8 million people refused to speak out against each other. And there were significant financial challenges. The average annual income in Kingston is less than US$3,000. The woman was searching for doctors with the expertise and willingness to provide medical legal opinions at a cost that Jamaican citizens could afford.

This brief but fortuitous conversation sparked a whirlwind of activity in two countries located thousands of miles apart. In Jamaica, three of the victims of malpractice were contacted and told that a lawsuit might be possible. The Gleaner, a Kingston newspaper, published an article headlined “A cure for medical negligence,” reporting that our Canadian doctors could “cut the culture of silence” that currently surrounded medical malpractice. They also reported that establishing accountability would encourage a culture of patient safety and improve health-care outcomes. The people of Jamaica held public demonstrations in the streets of downtown Kingston, demanding increased access to justice.

Here in Canada, we appealed to doctors across the country, asking for their help. Two doctors responded quickly and enthusiastically, generously offering to waive 100 per cent of their fee — Colin Birch, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at the Foothills Hospital in Calgary, and Jeff Ginsberg, professor of medicine and haematology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. Birch provided opinion on two of the cases — one involving the death of a young woman following a relatively minor surgical procedure, and the other, concerning a newborn who received terrible injuries resulting from delayed treatment of a postpartum infection. In the first case, the young woman died without access to basic services such as licensed physicians, lab tests and ultrasound. In the second case, delayed intervention ultimately resulted in disfigurement, hair loss and the cessation of breastfeeding of the newborn infant, which brought significant social and financial hardship to a young family with five children.

Ginsberg provided opinion on the third case, which involved the care provided to a young man suffering from sickle-cell anemia. His opinion highlighted the fact that complications of this disease are well known in Caribbean countries and can be effectively treated with universally available “low-tech” therapies such as IV fluids, antibiotics, monitoring of vital signs and blood transfusions. Sadly, these interventions were not provided and the young man died. Ginsberg said that reviewing this case prompted him to write a report unlike any other he had ever written. Both doctors based their opinions on an expected universal level of care while they struggled with illegibility in the records and a significant paucity of information. Two of the cases are anticipated to settle on the strength of the medical reports we provided. The third is expected to reach the Supreme Court of Jamaica later this year.

Several months after the “Jamaica Project” began, it was mentioned in casual conversation to Vancouver lawyer Angela Price-Stephens. She was excited and energized at the opportunity to bring justice and accountability within Jamaica’s health-care system and offered pro bono assistance to the lawyers involved. In March, Price-Stephens flew to Kingston at her own expense to support this extraordinary project and had this to say: “The law of Jamaica is based on English common law. However, subtle and distinct differences to the English (and Canadian) system make the law of Jamaica more hostile to would-be plaintiffs. One such barrier is that plaintiff’s counsel must present to the court expert evidence before receiving consent of the court to issue proceedings. This means an expert’s report must be obtained very early in the investigation process and the author of that report must be prepared to answer the court’s questions for the court to satisfy itself that the proposed claim has merit. This process would be familiar to our American colleagues at the bar, but not in the U.K. or Canada.”

This amazing, heartwarming and important journey has showcased kindness, generosity and a desire for safer health-care care around the world. The work is just beginning as the problems that exist in Jamaica exist in many other developing countries. The hope and expectation is that with sustained effort, Canadian doctors and lawyers can improve health care and access to justice for some of society’s most vulnerable victims.

Author: Chris Rokosh RN

Originally published in The Lawyer’s Weekly.