The recent court case, Ghiassi (Litigation guardian of) v. Singh 2017 ONSC 6541 focused on a rare, but serious complication of newborn jaundice; kernicterus. This case involved a preterm, male infant of East Indian descent who developed kernicterus in the hospital setting. The nurses were deemed liable for damages for failing to recognize and report signs of worsening jaundice.

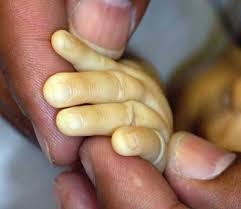

Newborn jaundice is common. It is, in fact, the most common newborn ailment requiring treatment. Babies are born with more red blood cells than adults, which gives them their red, ruddy color. These cells have a shortened lifespan and as they break down, bilirubin is produced as a natural byproduct. Bilirubin is an orange-yellow substance which can permeate the skin, eyes and inside of the mouth, turning them yellow, or jaundiced.

You may be familiar with this process of cell breakdown if you’ve ever watched a bruise turn from red to purple to yellow before slowly fading away. Jaundice occurs in approximately 50 to 60 per cent of full-term infants and up to 80 per cent of preterm infants. All infants are at risk for jaundice, but breastfeeding, family history, male infants, traumatic delivery, bruising, infection, poor feeding, prematurity, delayed passage of meconium and East Asian ethnicity increase the risk.

Normal or physiologic newborn jaundice typically appears between the second and sixth day of life. If it is apparent on the first day of life, before 24 hours of age, it is suspected to be pathologic, or caused by a disease process. Initially, a jaundiced baby might be slightly yellow, sleepy and reluctant to eat. As the level of bilirubin rises, the skin becomes increasingly yellow from head to toe. If bilirubin reaches high levels (hyperbilirubinemia) the baby may develop a high-pitched cry, respiratory distress, tenseness of the fontanels or “soft spots” on the head, muscle spasms, spasticity, fever and seizures.

Jaundice is visually assessed by applying slight pressure to blanch the skin on the baby’s forehead, nose or chest in a well-lit area, and by examining the whites of the eyes. If the skin or eyes appear yellow, a simple blood test can confirm the level of bilirubin in the blood. This visual assessment can be unreliable and subjective however, especially in dark skinned babies, so bilirubin testing may be necessary in high risk infants. If the level of bilirubin in the blood is elevated above certain predetermined thresholds, the baby is undressed and exposed to light in the form of sunlight or phototherapy. Additional feedings will be offered. Serial blood tests will be taken to measure the rise or fall of bilirubin. If the level of bilirubin reaches to critical levels, an exchange blood transfusion may be required.

Most of the time, jaundice comes and goes without complication. But in some situations, bilirubin reaches levels high enough to cross the blood/brain barrier. The resultant yellow staining of the brain is known as kernicterus, which is associated with acute or chronic bilirubin encephalopathies. Many infants who develop kernicterus will die. Those who survive may have permanent sequelae including movement or seizure disorders, eye gaze abnormalities, hearing loss, intellectual deficits and dental dysplasia.

Most of the time, jaundice comes and goes without complication. But in some situations, bilirubin reaches levels high enough to cross the blood/brain barrier. The resultant yellow staining of the brain is known as kernicterus, which is associated with acute or chronic bilirubin encephalopathies. Many infants who develop kernicterus will die. Those who survive may have permanent sequelae including movement or seizure disorders, eye gaze abnormalities, hearing loss, intellectual deficits and dental dysplasia.

Kernicterus was a major problem in North America before 1950. It was then nearly eradicated between 1973 and 1982 thanks to new guidelines and treatments which included routine bilirubin testing, widespread use of phototherapy and advances in transfusion medicine. But rates of kernicterus surged again in the 1990s, coinciding with early discharge programs which sent new mothers and babies home from hospital within 48 to 72 hours. The problem was that bilirubin levels, which peak at three to five days of life, were not being monitored in the community.

By 2009, kernicterus was identified as an “American Clinical Emergency.” In 2014, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute placed it eighth on its list of 15 “Never Events” (preventable events). It’s hopeful that current guidelines for assessing, testing and treating jaundice, both in the hospital and in the community, will result in a steady decrease in the number of cases. But the current incidence of kernicterus in Canada is uncertain, as is the threshold for bilirubin levels that cross the blood/brain barrier.

The Canadian Pediatric Society currently recommends bilirubin testing for all babies before 72 hours of age, careful assessment of risk factors, systematic diagnosis of jaundice with appropriate laboratory tests and adequate treatment. Kernicterus can still occur when there is a delay in treatment, failure to comply with current testing and treatment guidelines, when health care professionals don’t recognize the limitation of their visual assessments or ignore parental concerns, or without adequate follow-up in the community.

Chris Rokosh is a certified perinatal nurse and legal nurse consultant and is president and CEO of Connect Medical Legal Experts, a national company that provides health care expertise to lawyers involved in personal injury, medical malpractice and class action litigation. She was an expert witness retained by the plaintiffs in Ghiassi v. Singh.

This article originally appeared on The Lawyer’s Daily website published by LexisNexis Canada Inc.