This white paper is the first of three parts on the complex functions of brain, what happens when an injury is acquired and how to care for and manage a life-changing brain injury.

BY LINDA SIMMONS, RN BScN

Senior Nurse Life Care Planner, Connect Medical Legal Experts

This document will increase the health care professionals understanding of Acquired Brain Injury (ABI). ABI is defined as damage to the brain that is acquired after birth. It can affect cognitive, physical, emotional, social, or independent functioning. ABI is an umbrella term used to describe all brain injuries. ABI can result from traumatic brain injury (i.e. accidents, falls, assaults, etc.) and non-traumatic brain injury (i.e. stroke, brain tumours, infection, poisoning, hypoxia, ischemia or substance abuse).

The motor vehicle related accident clients that we at Connect Experts see with ABI have often resulted from a Traumatic Brain Injury and thus ABI’s that have resulted from a TBI will be the focus of this document.

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) is a life-changing event for the client, families, and their community. An ABI can affect all aspects of a person’s life including physical, emotional, psychosocial, and vocational potential. The impact can be pervasive and devastating.

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) is a life-changing event for the client, families, and their community. An ABI can affect all aspects of a person’s life including physical, emotional, psychosocial, and vocational potential. The impact can be pervasive and devastating.

Statistics continue to reveal the magnitude of injuries including ABI in Ontario. The Ministry of Health of Ontario (2007) has published some current statistics in regards to injuries that occur within our province. The lists below provide statistics, injury rates and oepidemiological data on TBI (ERABI, 2006).

TBI INJURY STATISTICS

Every 30 seconds someone visits an emergency department in Ontario because of an injury

Every 30 seconds someone visits an emergency department in Ontario because of an injury- Approximately 95% of all injuries are both predictable and preventable.

- Approximately one in every four emergency department visits in Ontario is injury-related, and among children aged 10 – 14, this increases to al

most one in two. - In 2004-2005, motor vehicle collisions were the leading cause of major trauma hospitalizations in Ontario at 44%, followed by unintentional falls at 34%

- Sport and recreation related injuries account for ten percent of major trauma cases in Ontario.

- Each year these injuries cost Ontario an estimated $5.7B in direct costs to the health system and lost productivity – almost as much as cance.

- The burden of injury is greater for some groups than others. In particular, children, youth, seniors, Aboriginal people and northern Ontarians are all at greater risk for injury than other Ontarians.

- Unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for children and youth in Canada.

In addition, injury rates are highest among toddlers and older children, with falls being the most frequent cause of emergency department visits and hospitalizations of children between 0-14 years old.

In addition, injury rates are highest among toddlers and older children, with falls being the most frequent cause of emergency department visits and hospitalizations of children between 0-14 years old.- Over 30% of alcohol-related motor vehicle collisions involved Canadians under the age of 25.

- For Ontarians over the age of 65, falls are by far the leading cause of injury-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and in-hospital deaths.

- In 2004/05, seniors accounted for 40% of injury-related hospitalizations.

- The rates of unintentional injuries are significantly higher among Aboriginal peoples.

- Injury is the leading cause of death for Aboriginal children, youth, and young adults in Canada.

TBI Epidemiology

- TBI of the leading cause of death and lifelong disability especially in children and adolescents

- Estimated number of brain injuries in Ontario is over 18,000 (4,000 occurring in children ages 0-14 years)

- TBI is three times more common in men and the highest rate of injury occurs in young men ages 15-24. This is related to risk taking activities, occupational hazards and violence related injury

- Incidence of TBI doubles between the ages of 5-14 years and peaks for both male and females during adolescence and early adulthood (250 per 100,000 of these 20% are moderate or severe TBI

- About 50% of TBI is due to MVA and related transportation accidents and often victims are young males 15-24 years of age

- TBI in children is related to child abuse, sporting accidents and fallsTBI in elderly is most commonly related to accidental falls

- Elderly have greater severity of injury and higher mortality rates

PROGNOSIS STATS

- About 50% of adults with severe TBI have a good recovery or moderate disability.

- Occurrence and duration of coma after a TBI are strong predictors of disability

- Patients whose coma exceeds 24 h, 50% have major persistent neurologic conditions

- About two to 6% remain in a persistent vegetativestate at 6 mos.

- Adults with severe TBI, recovery occurs most rapidly within the initial 6 mo. Smaller improvements continue for perhaps as long as severalyears.

- Children have a better immediate recovery from TBI regardless of severity and continue to improve for a longer period of time.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Brain

The brain is the control centre of our Central Nervous System (CNS). The CNS consists of the brain, spinal cord and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Together they control all aspects of daily living which includes: walking, talking, breathing, swallowing, taste, heart rate, thinking function, emotions, intellectual (cognitive) activities, learning, memory, how we perceive and understand our world and its physical surroundings. The amount of impairment a person will have following an ABI will depend on the type, location, and severity of the brain injury.

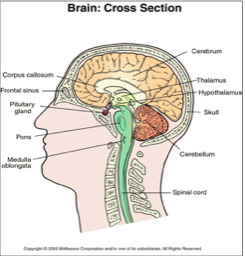

The anatomy of the brain consists of a

number of structures: Spinal Cord,

Brain Stem (Medulla Oblongata, Pons, and Midbrain), Reticular Formation, Cerebellum, Thalamus, Hypothalamus, Pituitary Gland, Corpus Collosum, and Cerebral Cortex. Diagram 1 (brain cross-section, above left) depicts a cross sectional view of the brain and the lobes of the Cerebral Cortex.

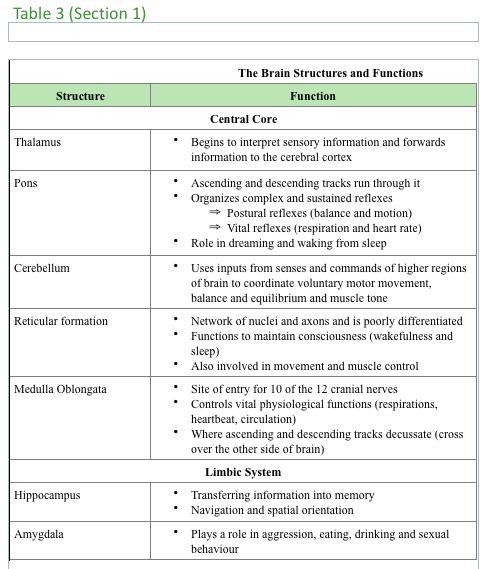

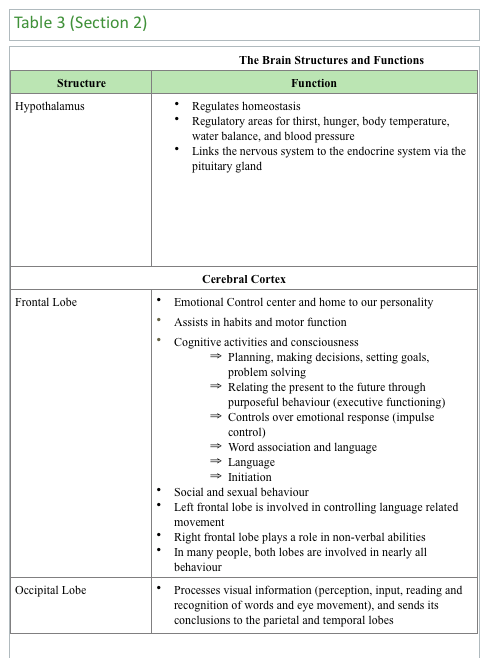

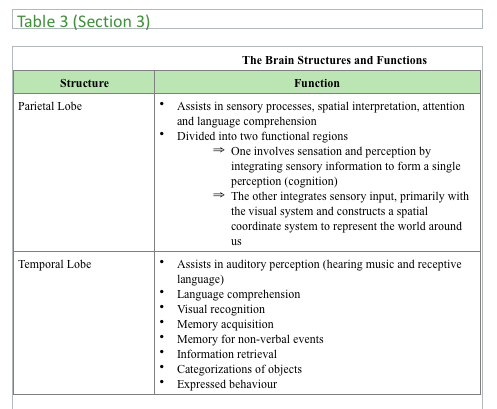

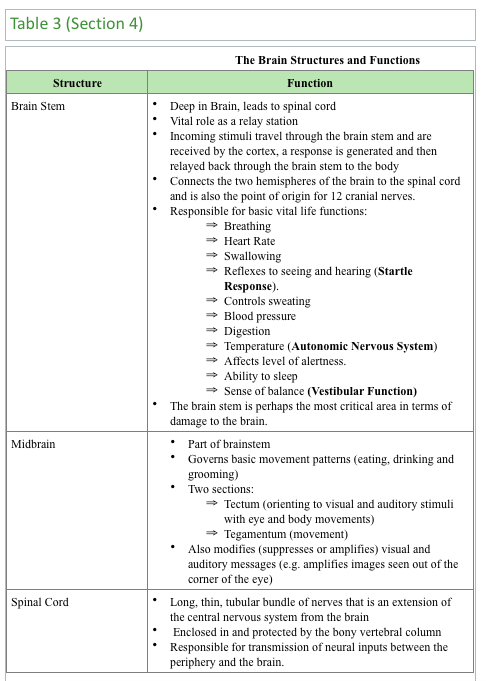

The brain is a unified whole, however areas have been identified within the brain that perform specific functions. The three identified areas are central core, limbic system, and cerebral cortex. The central core consists of thalamus, Pons, medulla oblongata, cerebellum, and reticular formation.

The five regions of the central core are responsible for life processes such as breathing, pulse, arousal, movement, balance, sleep, and the early stage of processing sensory information.

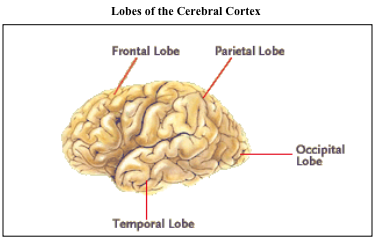

The limbic system consists of hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. This system is only found in mammals and controls motivated behaviour, emotional states and memory processes. The limbic system also regulates body temperature, blood pressure, blood sugar levels, hunger, thirst, sexual arousal, and the sleep/wake cycle. The cerebral cortex consists of frontal lobe, parietal lobe, occipital lobe, and temporal lobe. This structure is responsible for higher cognitive and emotional functions.

The cerebral cortex is divided into almost two symmetrical halves called the cerebral hemispheres with each hemisphere containing the four lobes.

These lobes oversee conscious experiences such as perception, emotion, thought and planning and unconscious cognitive and emotional

processes. Table 3, above and right, describes the specific function of the components of the central core, limbic system, and cerebral cortex.

The Skull

The brain is housed in the cranial vault. The contour of the inner aspect of the vault (skull) is variable. The occipital area (back of the skull) is smooth, however, other areas are highly irregular as in the frontal-orbital and temporal area. The bones also are etched tracts for major blood vessels. The middle meningeal artery is located on the temporal bone.

- This is where the skull is thinnest; therefore, temporal bone fractures can cause the artery to be torn, causing an epidural hematoma. The very nature of the skulls contour can affect the severity of the injury

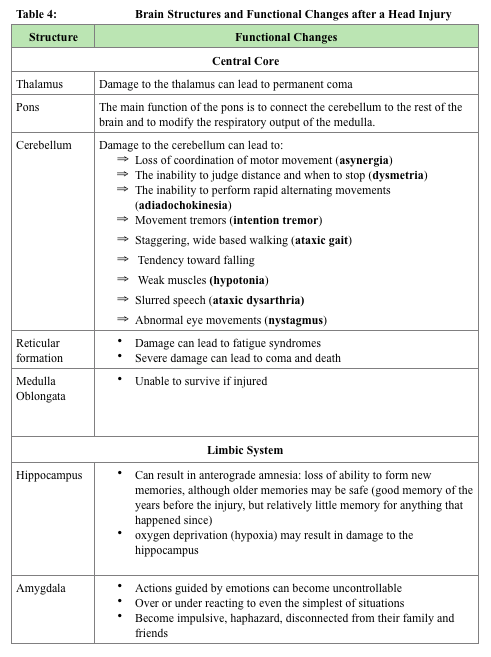

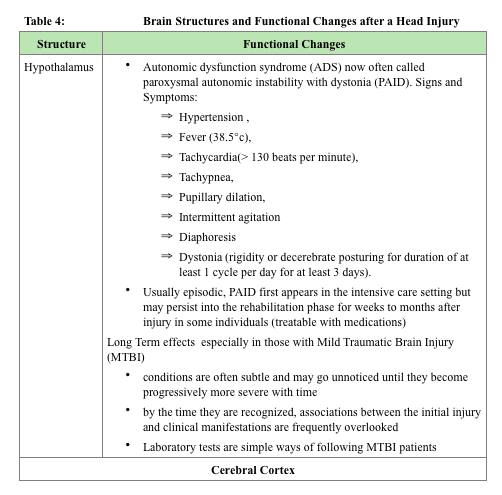

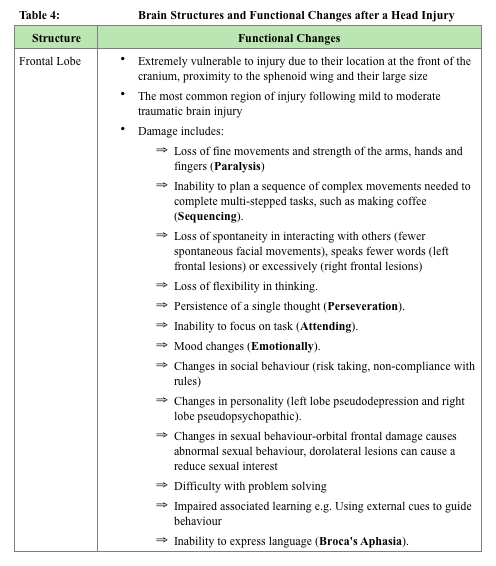

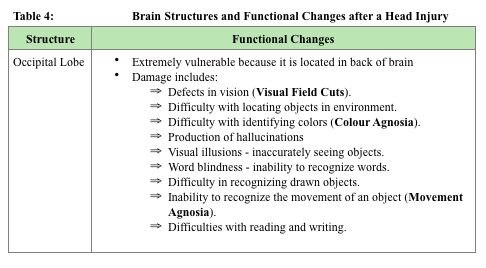

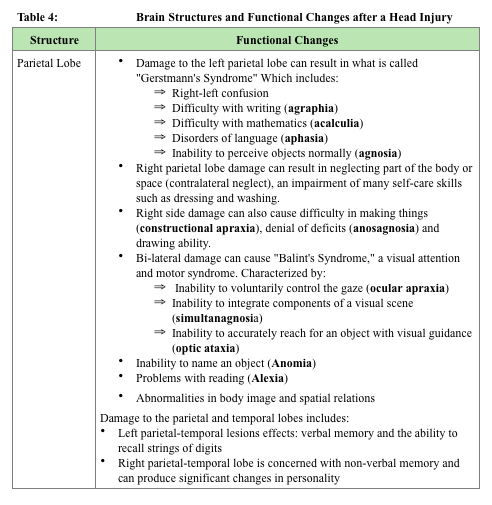

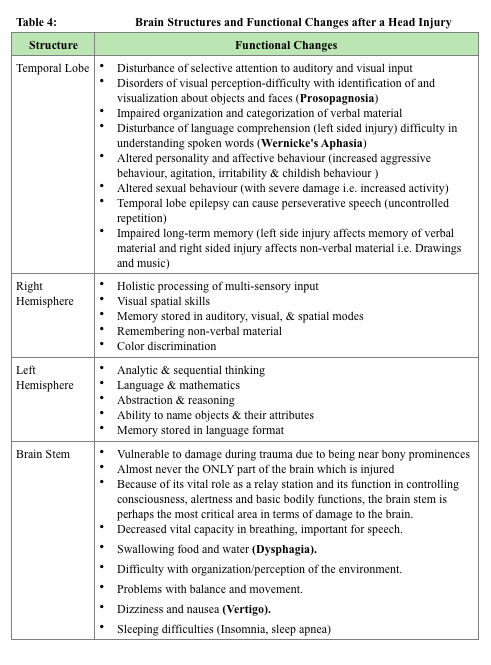

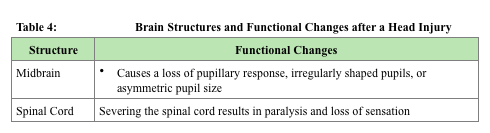

The Brain Structures and Functional Changes after a Head Injury

When a person experiences a brain injury, depending on the location, the injury can affect the disabilities that the patient will have. The brain may be injured in a specific location or the injury may be diffused to many parts of the brain. The extent of a brain injury can be uncertain and varies widely for each individual therefore a unique treatment plan is required for each individual.

Table 4 (parts 1-7, below) outlines the problems that are encountered based on the location of the injury.

Glossary of Terms

- Agnosia – is a loss of ability to recognize objects, persons, sounds, shapes, or smells while the specific sense is not defective nor is there any significant memory loss

Anterograde amnesia – loss of ability to form new memories, although older memories may be safe (good memory of the years before the injury, but relatively little memory for anything that happened since)

Anterograde amnesia – loss of ability to form new memories, although older memories may be safe (good memory of the years before the injury, but relatively little memory for anything that happened since)- Aphasia – loss of the ability to produce and/or comprehend language, due to injury to brain areas specialized for these functions. Depending on the area and extent of the damage, someone suffering from aphasia may be able to speak but not write, or vice versa, or display any of a wide variety of other deficiencies in language comprehension and production, such as being able to sing but not speak. Aphasia may co-occur with speech disorders such as dysarthria or apraxia of speech.

- Apraxia – loss of the ability to execute or carry out learned purposeful movements, despite having the desire to and the physical ability to perform the movements

- Ataxic (ataxia) – gross in-coordination of muscle movements

- Broca’s asphasia – language is reduced to disjointed words and sentence construction is poor

- Comminuted Skull Fracture – skull splintered or shattered into pieces

- Depressed Skull Fracture – fragment of the skull is depressed with or without tearing of dura mater [three layers of the meninges surrounding the brain and spinal cord]

Dysarthria – is a speech disorder that is due to a weakness or in-coordination of the speech muscles. Speech is slow, weak, imprecise, or uncoordinated.

Dysarthria – is a speech disorder that is due to a weakness or in-coordination of the speech muscles. Speech is slow, weak, imprecise, or uncoordinated.- Dystonia – involuntary contractions of muscles resulting in twisting and repetitive movements. Sometimes they are painful.

- Diffuse visual field defects – overall blurred vision

- Emotionally Labile – refers to the pathological expression of laughter, crying or smiling

- Linear Skull Fracture– single fracture line

- Multiple field loss – areas of darkness that appear to be scattered around objects

- Open Depressed Skull Fracture – opening of the skull as a result of comminuted depressed skull fracture and tearing of the dura mater and the scalp

- Pseudodepression – condition following a massive lesion in the frontal lobe of the brain, characterized by apathy, indifference, and loss of initiative but no experience of depression

- Pseudopsychopathic – characterized emotional and social instability, aggressive behaviour (at times), cognitive disturbances described as a special form of incoherence, abnormal social behaviour in the form of social adhesiveness, carelessness and a certain proneness to criminality

- Tunnel vision (constriction) – objects in the center of the visual field are visible, but those on the edges are not

- Visual Field Cuts – complete or partial loss of peripheral vision. People with visual field loss may have problems seeing objects out of the corner(s) of their eyes, losing their place while reading, being startled by people or objects moving toward them, or bumping into people and objects.

TABLE 4, PARTS 1-7

REFERENCES

Evidence-Based Review of Moderate to Severe Acquired Brain Injury (ERABI) (2006). Retrieve March 24, 2008 from http://www.abiebr.com/index_home.html

Centre for Neuro Skills TBI Resource Guide (2006). The brain map. Retrieved March 3, 2008 from http://www.neuroskills.com/brain.shtml

Deitch, E. A., & Dayal, S. D. (2006). Intensive care unit management of the trauma patient. Critical Care Medicine, 34 (9), 2294-2301.

Discovering Psychology (2008). The human brain. Retrieved on March 3, 2008 from http://www.learner.org/discoveringpsychology/brain/brain_flash.html.

Fakhry, S. M., Trask, A. L., Waller, M. A., & Watts, D. D. (2004, March). Management of brain-injured patients by an evidence-based medicine protocol improves outcomes and decreases hospital charges. The Journal of Trauma Injury, Infection and Critical Care, 56(3), 493-500.

Granacher, R. P. (2005). Traumatic brain injury: Methods for clinical and forensic neuropsychiatric assessment. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Hebb, M. O., Clarke, D. B., & Tallon, J. M. (2007, June). Development of provincial guideline for the acute assessment and management of adult and pediatric patients with head injuries. Canadian Journal of Surgery, 50 (3), 187-194. Retrieved February 26, 2008, from http://www.cma.ca/index.cfm/ci_id/52773/la_id/1.htm

Karol, R. L. (2003). Neurpsychosocial intervention: The practical treatment of severe behavioural dyscontrol after acquired brain injury. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Marik, P. E., Varon, J., & Trask, T. (2002, August). Management of head trauma. Chest, 122(2), 699-711. Retrieved February 22, 2008, from http://chestjournal.org/cgi/content/abstract/122/2/699

Ministry of Health Promotion (2007). Ontario’s injury prevention strategy: Working to together for a safer, healthier Ontario. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from http://www.mhp.gov.on.ca/english/injury_prevention.pdf

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (2002). Traumatic brain injury: Hope through research. Retrieved February 21, 2008, from http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm

The Merck Manuals Online Medical Manual (2007). Retrieved March 1, 2008, from http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec21/ch310/ch310a.html

Nolan, S. (2005, April-June 2005). Traumatic brain injury: A review. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 28(2), 188-194.

The Brain Injury Recovery Network (2003). Injury overview. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from http://www.tbirecovery.org/overview.htm

The Rancho Levels of Cognitive Functioning (1990). Family guide to the rancho levels of cognitive functioning. Retrieved February 20, 2008 from http://www.rancho.org/patient_education/bi_cognition.pdf

Zoellner, J. L. (2003). Craniocerebral trauma. In J. V. Hickey (Ed.), Clinical practice of neurological & neurosurgical nursing (5th ed., pp. 373-403). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.